Tuesday, 30 September 2014

Monday, 29 September 2014

John of Canterbury

John of Canterbury

Aka John of Poitiers, John of Belmeis, Jean de Belmeia, Jean aux Belles-Mains, Jean des Bellesmains and Jean de Bellesmes.

John of Canterbury - Oxford DNB

Actes Du Colloque International de Sedieres. Charles Duggan: Bishop John and Archdeacon Richard of Poitiers. Their roles in the Becket Dispute and its Aftermath: Editions Beauchesne. pp. 71–.

John of Oxford

Called by Becket 'usurper' of the deanship of Salisbury

While it was unlikely that he was personally responsible for the drafting of the Constitutions of Clarendon, it seems very likely that he was one of a group responsible for commissioned by Henry II to delineate the ecclesiastical customs od his grandfather's reign.

Council and Synods Part I Volume II

Dorothy Whitelock; M. Brett; Christopher Nugent Lawrence Brooke; Frederick Maurice Powicke (1981). Councils & Synods, with Other Documents Relating to the English Church: A.D. 871-1204. I. Part I Volume II. Clarendon Press. pp. 852, 877.ISBN 978-0-19-822394-8.

References

John of Oxford - Wikipedia

John of Oxford - DNB

Oxford, John of (DNB00) - Wikisource

Deans Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300 volume 4 (pp. 7-12)

NORWICH - Bishops (originally of Elmham and Thetford) Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300 volume 2 (pp. 55-58)

Michael J. Franklin (1995). "Christopher Harper-Bill: John of Oxford, diplomat and bishop". Medieval Ecclesiastical Studies: In Honour of Dorothy M. Owen. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 83–105. ISBN 978-0-85115-384-1.

While it was unlikely that he was personally responsible for the drafting of the Constitutions of Clarendon, it seems very likely that he was one of a group responsible for commissioned by Henry II to delineate the ecclesiastical customs od his grandfather's reign.

Council and Synods Part I Volume II

Dorothy Whitelock; M. Brett; Christopher Nugent Lawrence Brooke; Frederick Maurice Powicke (1981). Councils & Synods, with Other Documents Relating to the English Church: A.D. 871-1204. I. Part I Volume II. Clarendon Press. pp. 852, 877.ISBN 978-0-19-822394-8.

While it was unlikely that he was personally responsible for the drafting of the Constitutions of Clarendon [In MTB 195 and 196/CTB 79 and 80 Becket blames Richard de Lucy and Jocelin de Balliol for this]

However, it seems very likely that he was one of a group responsible for commissioned by Henry II to delineate the ecclesiastical customs od his grandfather's reign.

[but in the same letter to the Pope he names John of Oxford as excommunicate for communicating with the schismatic Reinald of Cologne and for usurpation of the deanery of Salisbury.]

John of Oxford - Wikipedia

John of Oxford - DNB

Oxford, John of (DNB00) - Wikisource

Deans Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300 volume 4 (pp. 7-12)

NORWICH - Bishops (originally of Elmham and Thetford) Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300 volume 2 (pp. 55-58)

Michael J. Franklin (1995). "Christopher Harper-Bill: John of Oxford, diplomat and bishop". Medieval Ecclesiastical Studies: In Honour of Dorothy M. Owen. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 83–105. ISBN 978-0-85115-384-1.

Sunday, 21 September 2014

Plan de la ville et des faubourgs de Sens

|

| Sens |

|

| Cathédrale de Sens 1828 |

References

Maximilien Quantin (1842). Notice historique sur la construction de la cathédrale de Sens, rédigée sur les documents originaux existant aux archives de la préfecture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sens_Cathedral

http://mappinggothic.org/building/1067#/

Friday, 19 September 2014

Becket's Spy Ring

Extract from a letter from John of Salisbury to Bartholemew, bishop of Exeter

John Allen Giles (1846). The Life and Letters of Thomas À Becket: Now First Gathered from the Contemporary Historians. Whittaker and Company. pp. 400–.

"Everything around us is so beset with spies and snares, that good and honest people do not dare to express their thoughts freely to one another, either by word of mouth or by letter. Iniquity is daily forming paltry schemes against innocence: conscience is constantly goading it on, and so all men and all things around them abound with treachery and suspicion."

Extract from

Frank Barlow (1990). Thomas Becket. University of California Press. pp. 129–30. ISBN 978-0-520-07175-9.

Thomas was always a fighter. He took up the struggle immediately and

pursued it to the end. He quickly established a widespread intelligence

network. Herbert was probably his spy-master and the outstations were

at Rheims (John of Salisbury), which was well placed to get news from

Germany, especially through Gerard la Pucelle, Rouen (Nicholas, prior and

guestmaster of the hospital of Mont-St-Jacques) and Poitiers (Bishop John).

The main apparent weaknesses (it has to be remembered that some secret

sources may have been successfully concealed) were the lack of really productive

agents in the papal and royal courts. Although Master Lombard joined

the curia probably at the beginning of 1169 there was never a great flow

of top-level information. And, although Thomas always had sympathizers

in the royal court, Walter de Lisle was uncovered at the end of 1166 and

the trickle of news seems never to have been sufficient to give the exiles

a full understanding of the royalist plans and manoeuvres. Also, Nicholas

soon pulled out and in the end the two Johns were discouraged. Thomas

then relied increasingly on William, archbishop of Sens, and other French

bishops and supporters. The dossier of this largely secret, and from the

king's point of view treasonable, correspondence is enormous: some 700

items; and most business was done by word of mouth.

Herbert of Bosham mentions there were secret sympathizers in the royal court,

Materials Vol iii. p. 412.

References

Frances Andrews; Brenda M. Bolton; Christoph Egger; Constance M. Rousseau (2004). Pope, church, and city: essays in honour of Brenda M. Bolton. Anne J. Duggan: Thomas Becket's Italian Network: BRILL. pp. 177–. ISBN 90-04-14019-0.

Charles Donahue jun., ‘Pucelle, Gerard (d. 1184)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49666

Charles Donahue jun., ‘Pucelle, Gerard (d. 1184)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49666

Wednesday, 17 September 2014

The Nature of Hagiography

When composing the Life of a Saint, the hagiographer's purpose, the hagiographic method, is to place a very large emphasis, in its pattern of composition, on narrative rather than on historical fact. The subject's saintly life and attitude to faith and God becomes more important, and, of course, the miracles that were said to flow from his/her death and relics. The story of saints were intended for use by the Church as part of its moral teaching, as well the process for declaring a person to be a saint after their death. Historical accuracy takes second place.

Trained to read scripture, clerics were taught to interpret historical and biographical events in a religious and moralistic light. Being literate theirs was a religious interpretation of history, using the language of the church. Further the hagiographic ideal is that a saint's life should be lived in the Imitation of Christ. This is how hagiographers like to represent them. This style of the writing up of the biographies of saints has always been an important element of Christian theology. one which incorporates the primary concerns of ethics and spirituality. References to the concept of the Imitation of Christ, and the method of storytelling are found in the earliest of Christian documents, such as the Pauline Epistles. Martyrdom was the highest religious ideal of all. Christ died on the cross for the salvation of our souls. Saints who are martyrs and who died for their beliefs, and for the ideals of the Christian Church clearly meet with this criterion.

The evolution of a cult of a saint is a legitimate study for a scientific historian, its effect on a society. the question why someone became a saint. The provable and confirmable events in the life of a "political saint" like Becket are also legitimate to study, and the history which surround them. Selective recourse to hagiographies may be necessary, as the only documents necessarily available.

We are limited in the study of Becket by the fact that in his time nearly all the material assembled after his murder was done for hagiographical purposes.

Becket was the saviour of the freedom of the Church its privileges. He had died brutally in and for this cause. His story was the story of a passion and the direct reason for his promotion to sainthood. The hagiographical method of constructing the Life and Passion of saint was to write it up as if it compared directly to Christ's own life and passion. Christ's story was the model for these stories.

Part of the hagiographical method of Becket's time was to relate a saint's story as a legal struggle, as a trial in life and death. The lives of Becket are oratory. His story is related rhetorically as if it were a trial by verbal battle. This was the Age of Faith. Becket has to be right if he died the death of a martyr. Becket is a knight epically and heroically defending the Church's rights and privileges. Becket is the wizard sweeping aside evildoers by means of the spell of excommunication: Becket draws the ecclesiastical sword of St. Peter on numerous occasions. Much is made of this in the hagiography. The Becket story is full of people swearing oaths to this or that. Oaths are magical. Miracles are magic and saints are magicians. Becket transformation from wordly chancellor to dedicated archbishop was magic.

During the first millennium of the Church, the cultus (the Church formally acknowledging the holiness) of a local saint was promulgated and cultivated by and under the authority of the Bishop of the diocese in which the saint had lived or worked, perhaps also acknowledging the popular acclaim by the people of the saint concerned. Many saints, however gained devotion even outside their respective dioceses and became honoured by the universal Catholic Church, though without any formal canonization process. Beginning in the 10th and 12th centuries in order promote better standards in the declaration of saints the Popes began to exercise a more direct role in the canonization process, reviewing bishops' determinations, criticising them if their decision was too rash, and even overriding their decisions and ordering the locally canonized saints struck from the calendar. This centralizing tendency continued until Pope Alexander III issued a bull in 1170 reserving all canonizations to the Holy See as its exclusive right. Becket has to be one of the first saints declared under Pope Alexander's new rules.

The historian's purpose, however, is not to make anyone a national hero, or a saint, or to judge what or who was good or bad, nor to criticise historical holocausts, but to organise and make sense of the events that have occurred in the past. Interpretations of these and statements about lessons for the future must clearly be identified as personal opinion.

References

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagiography

Seminar VII Hagiography - http://goo.gl/BiaAEN

An Ecclesiastical Epic: Garnier de Pont-Ste-Maxence's "Vie de Saint Thomas le Martyr"

Timothy Peters

Mediaevistik

Vol. 7, (1994), pp. 181-202

Published by: Peter Lang AG

Article Stable URL:http://www.jstor.org/stable/42584180

http://thehistorystudent.weebly.com/medieval/ritual-behaviour-and-symbolic-communication-in-the-dispute-between-thomas-becket-and-king-henry-ii

John Anthony Burrow; Ian P. Wei (2000). Medieval Futures: Attitudes to the Future in the Middle Ages. Phyllis B. Roberts: Prophecy, Hagiography and St Thomas of Canterbury: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-85115-779-5.

Gerd Althoff; Johannes Fried; Patrick J. Geary; German Historical Institute (Washington, D.C.) (2002). Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography. The Variability of Rituals in the Middle Ages: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-521-78066-7.

Timothy Reuter (2006). Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities. Velle sibi fieri in forma hac: Cambridge University Press. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-1-139-45954-9.

History and the Written Word in the Angevin Empire

(c. 1154–c. 1200)

William Henry Jonathan Bainton

(c. 1154–c. 1200)

William Henry Jonathan Bainton

etheses.whiterose.ac.uk-1233-1--bainton-thesis-submitted.pdf

History of the Devil's Advocate

Pope Alexander III and the Canonization of Saints

E. W. Kemp

History of the Devil's Advocate

Pope Alexander III and the Canonization of Saints

E. W. Kemp

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society

Fourth Series, Vol. 27, (1945), pp. 13-28

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678572

Fourth Series, Vol. 27, (1945), pp. 13-28

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678572

Saturday, 13 September 2014

Some Maps: Gravelines, St. Omer and Clarmarais

|

| Oye and Gravelines |

|

| Clairmarais and St Omer |

Clairmarais -Wikimapia

Saint Bertin's Abbey in Saint Omer - Wikimapia

References

Zoomable map: Gallica Map of Comté de Bologne

Friday, 12 September 2014

Council of London 1075

Some of the Canons of the Council of London 1075, Lanfranc presiding

The first canon decreed where the bishops should all sit. They decided that the Archbishop of York ought to sit at the right hand of Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London on the left, then the Bishop of Winchester should sit next to the Archbishop of York. However if the Archbishop of York was away then the Bishop of London should then sit on the right of Canterbury and Winchester on the left.

Monks should conform to the rule of St. Benedict.

By the decrees of Popes Damasus and Leo, and by the Councils of Sardica and Laodicea, bishops' sees should not be in vills, they should be in cities.

That no one should buy, or sell sacred orders or church office to the cure of souls because this crime was originally, condemned by the Peter the Apostle in the case of Simon Magus and afterwards forbidden under threat of excommunication by the holy fathers.

That by the Councils of Elvira and Toledo XI no bishop or abbot or any of the clergy should judge a man to be put to death or to mutilation, nor favour with his authority those who so judge.

References

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Council_of_London_in_1075

The first canon decreed where the bishops should all sit. They decided that the Archbishop of York ought to sit at the right hand of Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London on the left, then the Bishop of Winchester should sit next to the Archbishop of York. However if the Archbishop of York was away then the Bishop of London should then sit on the right of Canterbury and Winchester on the left.

Monks should conform to the rule of St. Benedict.

By the decrees of Popes Damasus and Leo, and by the Councils of Sardica and Laodicea, bishops' sees should not be in vills, they should be in cities.

That no one should buy, or sell sacred orders or church office to the cure of souls because this crime was originally, condemned by the Peter the Apostle in the case of Simon Magus and afterwards forbidden under threat of excommunication by the holy fathers.

That by the Councils of Elvira and Toledo XI no bishop or abbot or any of the clergy should judge a man to be put to death or to mutilation, nor favour with his authority those who so judge.

References

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Council_of_London_in_1075

Henry Gee; William John Hardy. Documents Illustrative of English Church History. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-115-67404-1.

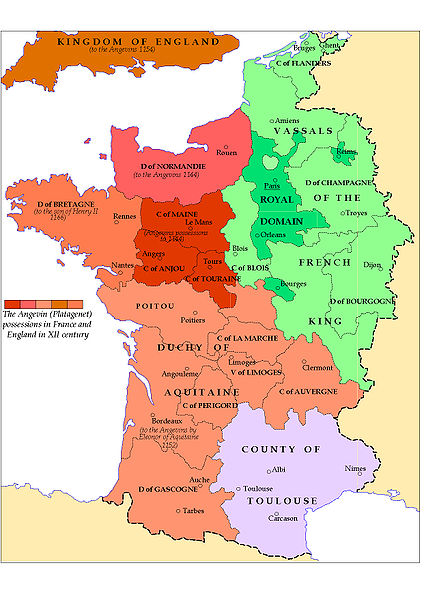

Angevin Empire

In its fullest extent, the Angevin Empire comprised the Kingdom of England, the Lordship of Ireland, the Duchy of Normandy and the Duchy of Aquitaine (the duchy of Aquitaine, which included the County of Poitiers, the Duchy of Gascony, the County of Périgord, the County of La Marche, the County of Auvergne and the Viscountcy [shrievalty] of Limoges), which were the lands belonging to his wife, Eleanor of Acquitaine, and the County of Anjou (which included the County of Maine and the County of Tours) which he inherited from his parents. The Plantagenets also had influence in the Duchy of Brittany, in the Welsh independent principalities, in the Kingdom of Scotland and the County of Toulouse, although these territories were not formally part of the empire. The King of Scotland paid homage to Henry II of England for the lands he held in England.

The Lord Rhys of Deheubarth in south Wales, and Owain ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, were made to swear fealty to Henry II in 1163, at Woodstock, but broke their oaths in 1165. So Wales was never really part of the empire.

In the Treaty of Falaise 1174 King William of Scotland was made to swear that Scotland would thereafter be subordinate to the English crown.

In 1155, Pope Adrian IV, issued a papal bull (known as Laudabiliter) that gave Henry II permission to invade Ireland as a means of strengthening the Papacy's control over the Irish Church. During 1171, Henry II landed an army in Waterford to ensure his continuing control over the preceding Norman force. In the process he took Dublin and had accepted the fealty of the Irish kings and bishops by 1172, so creating the Lordship of Ireland, which formed part of his Angevin Empire.

It is significant that Henry II and his sons and their lands in France were not outright kings of these territories, but only held these as fiefs of the King of France, to whom on several occasions they did homage for them.

References

Angevin Empire - Wikipedia

Empire Plantagenêt -Wikipédia

Historical Atlas of Britain : Internet Archive

Atlas historique : de l'apparation de l'homme sur la terre à l'ère átomique : Hilgemann, Werner - Internet Archive p.154-

The Making of the Angevin Empire

C. Warren Hollister and Thomas K. Keefe

Journal of British Studies

Vol. 12, No. 2 (May, 1973), pp. 1-25 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/175272

John France (2002). Western Warfare In The Age Of The Crusades, 1000-1300. Chapter 4 Warfare and Authority: Routledge. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-135-36507-3.

2nd May 1156: King Henry II did homage to Louis for Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine.

George Garnett (1994). Law and Government in Medieval England and Normandy: Essays in Honour of Sir James Holt. J.O. Prestwich: Military Intelligence Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-521-43076-0.

George Garnett (1994). Law and Government in Medieval England and Normandy: Essays in Honour of Sir James Holt. J.O. Prestwich: Military Intelligence Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-521-43076-0.

The Scholar's History of England ... : James H Ramsay Volume II Angevin Empire

Daniel Power (16 December 2004). The Norman Frontier in the Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-521-57172-2.

Christopher Harper-Bill (1995). Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1994. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-0-85115-606-4.

The Problem of Survival for the Angevin "Empire": Henry II's and His Sons' Vision versus Late Twelfth-Century Realities

Author(s): Ralph V. Turner

Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 1 (Feb., 1995), pp. 78-96

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2167984

The Problem of Survival for the Angevin "Empire": Henry II's and His Sons' Vision versus Late Twelfth-Century Realities

Author(s): Ralph V. Turner

Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 1 (Feb., 1995), pp. 78-96

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2167984

Fanny Madeline, « Les processus d’identification et les sentiments d’appartenance politique aux frontières de l’empire Plantagenêt », Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes [En ligne], 19 | 2010, mis en ligne le 30 juin 2013, consulté le 16 septembre 2014. URL : http://crm.revues.org/11985

Table of the Fiefdoms of France

Jacob Nicolas Moreau (1784). Principes

de morale, de politique et de droit public, puisés dans l'histoire de

notre monarchie ou Discours sur l'histoire de France. Imprimerie Royale. pp. 487–.

E.A. Freeman’s review of Kate Norgate's England under the Angevin Kings,

E.H.R., 2:8, 1887, pp. 774-780

England Under the Angevin Kings Volume 1 Norgate, Kate

England Under the Angevin Kings Volume 2 Norgate, Kate

Maurice Powicke (1999). The Loss of Normandy: 1189 - 1204 ; Studies in the History of the Angevin Empire. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5740-3

Francisque Michel (1837). Anglo-Norman Poem on the Conquest of Ireland by Henry the Second. W. Pickering.

Laudabiliter - Wikipedia

Richard Huscroft (26 April 2016). Tales From the Long Twelfth Century: The Rise and Fall of the Angevin Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18728-1.

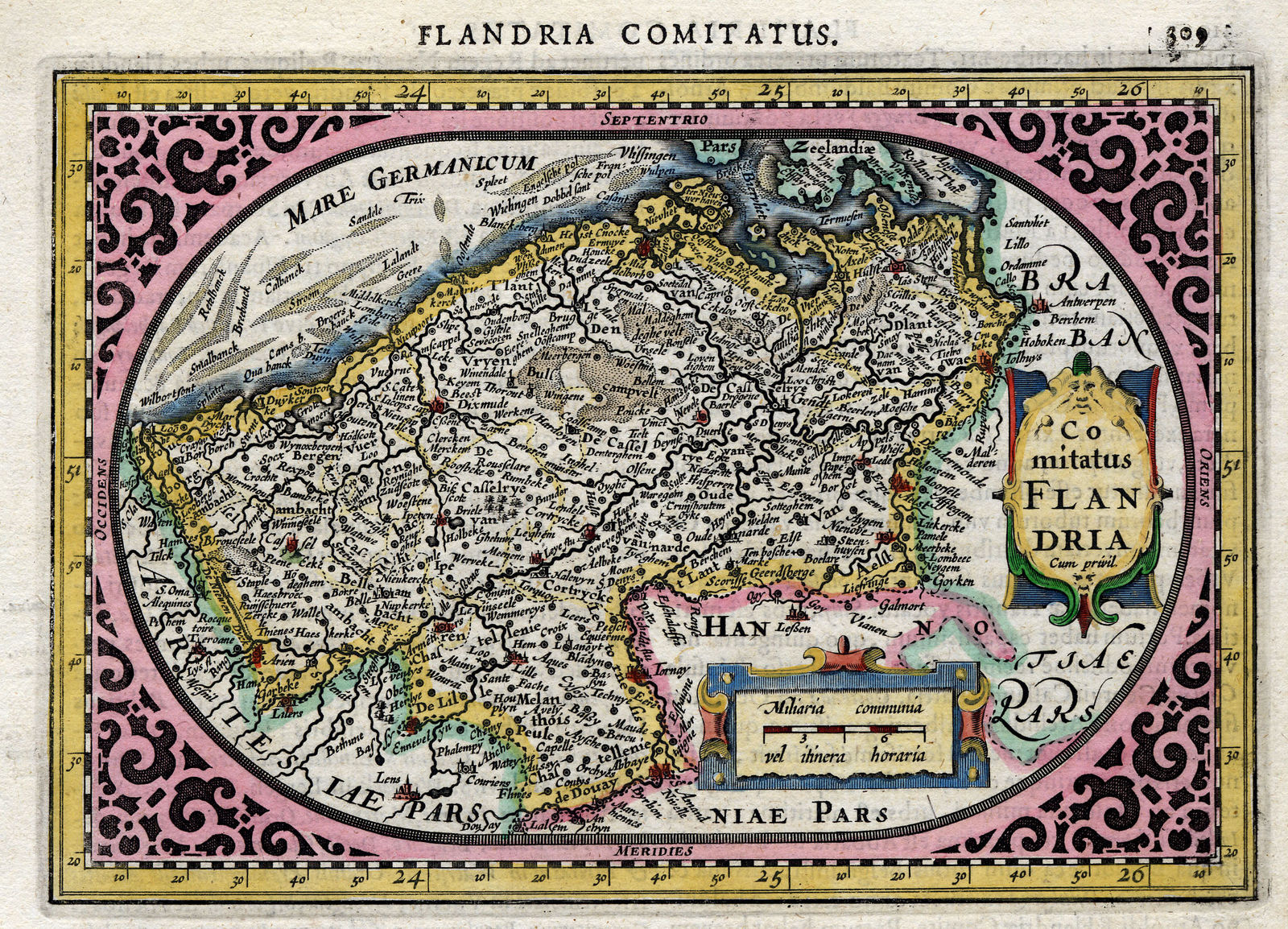

Map of Flanders

|

| Flandria |

County of Flanders - Wikipedia

History of Flanders - Wikipedia

Map of Flanders, Picardy 1777 http://bit.ly/1pwALGk

http://bit.ly/1pwB7wG

Map of Comté de Artois

Philip I, Count of Flanders - Wikipedia

| |

| Land Reclaimed in Flanders |

J. Buisman (1995). Duizend jaar weer, wind en water in de Lage Landen: Tot 1300. Van Wijnen. ISBN 978-90-5194-075-6

Eljas Oksanen (2012). Flanders and the Anglo-Norman World, 1066-1216. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76099-7.

Thursday, 11 September 2014

Monday, 8 September 2014

Map Comté de Toulouse

Saturday, 6 September 2014

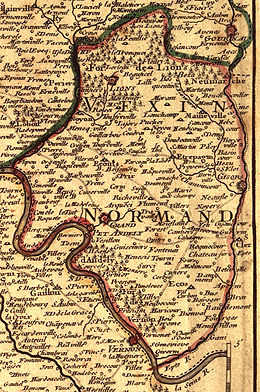

Map of the Vexin

|

| Vexin Normand |

| Vexin François | ois |

http://bit.ly/1pwBEyx

Carte Les Environs de Paris 1712 http://bit.ly/1pwBd7u

http://bit.ly/1pwBw25

Vexin — Wikipédia

Vexin français

Vexin normand

Amable Tastu (1837). Cours d'histoire de Frances, 1. Convention fait a Messine en Sicilie entre Phillipe August Roi de France et Richard, Roi de l'Angleterre: Larigne. pp. 317–.

Daniel Power (16 December 2004). The Norman Frontier in the Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-521-57172-2.

Christopher Harper-Bill (1995). Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1994. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-0-85115-606-4.

Fanny Madeline, « Les processus d’identification et les sentiments d’appartenance politique aux frontières de l’empire Plantagenêt », Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes [En ligne], 19 | 2010, mis en ligne le 30 juin 2013, consulté le 16 septembre 2014. URL : http://crm.revues.org/11985

.jpg)